- Home

- Nonie Darwish

Now They Call Me Infidel Page 8

Now They Call Me Infidel Read online

Page 8

Four

Marriage and Family Dynamics

My mother had four daughters to marry off.

I was just a teenager when they started coming: nervous fathers and mothers with an embarrassed son in tow, sitting on our salon couch making polite conversation with my mother, looking for a suitable wife and daughter-in-law.

We girls would look on through a crack in the door, trying to suppress our giggles as we surveyed and made fun of the young men who were our marriage “prospects.” There would be sneers of “eeuw,” nearly all of these boys were distasteful to us. We had dreams of romance and true love dancing in our heads, not financial negotiations and practical considerations.

Fortunately, my mother always came up with polite excuses. Her girls were too young. They were in school. They needed to finish college. I would console myself that I was safe from the fate of an arranged marriage at least until I graduated from the American University in Cairo.

Before these visits, the older women in the family would give us advice on how to present ourselves in front of the potential groom’s family. Stay quiet, we were told. My grandmother always emphasized that young ladies should never give opinions or talk back. Just offer coffee or tea, sit up straight, don’t cross your legs, and smile. She always said, “The best one is the quiet one, the one that is hardly seen or heard, the one that does not argue or rock the boat, the one that wants to please.” I was often admonished, “Look at your cousin [or this or that girl]. She sits quietly like a lady when there is company in the salon [our name for the guest living room].” We were told those who are quiet and obedient get the good husbands, and those who are not, get what they deserve! I often did not meet these criteria. I asked too many questions and had a big mouth compared to some of the “good” girls I was constantly being compared to. Even though I knew that my mother and grandmother loved me and thought I was very talented, their advice often hurt and confused me. Our upbringing did not allow us to convey dissatisfaction or learn how to say no or express hurt feelings. All of that was taboo for a nice young Muslim girl.

In the Muslim world, most marriages are arrangements between families. This is simply how you get married. Muslim women have very few choices when it comes to marriage as compared to Western women. We are deprived of dating, falling in love, and even innocent communication with boys. Furthermore, Muslim women often face an array of family tragedies that result from Islamic marriage and divorce laws. These laws are simply stacked against women while giving total freedom and power to men. It is a tragedy that begins with oppression of women but ends up in a complex family dynamic that negatively impacts the whole family—men included—and indeed Muslim society as a whole.

After graduating from college, I began wondering about how and when I would get married. I did want to someday marry and have children. But I hated the idea of marrying someone I didn’t know, arranged through the family, no matter how well meaning the effort. I looked around me. I didn’t want to be condemned to the same destiny as the many unhappy married Egyptian women I knew. However, I understood the reality of the Middle East and that I was probably going to get married the old-fashioned way, through the family.

After college, at age twenty-one, I finally yielded to the idea of marriage and accepted an engagement with a perfect stranger who was recommended by my aunt as a great catch from a wealthy family. After the engagement party, his parents invited me to their home and we were supposed to go out to a restaurant for dinner. His mother handed her son and me a shirt to iron for him before leaving. First of all, growing up with maids to perform most of the household duties, I didn’t really know how to iron. But I gave it a try. How hard could it be? Nervous and excited, and busy talking with my new fiancé, I burned the shirt. His mother came in and had a fit, sarcastically saying that obviously neither one of us could take care of ourselves, let alone be responsible for a home.

To make a long story short, the next day I handed back the ring. It was one of the shortest engagements in the Middle East.

Egyptian girls are no different than girls all over the world. They long for love and romance. One could always hope and dream, for there were some exceptions in which marriage took place after a secret love relationship. Sometimes girls and boys fell in love and would meet behind their parents’ backs, in dark movie theaters or street corners where they hoped they would not be seen by relatives or family friends.

However, carrying on such a relationship involved serious risks. If they were seen by a friend, neighbor, or relative, the girl’s reputation could be damaged for life and impact her whole family, especially the males in the family, whose honor depends on the chastity of the women in the family. And in Arab cultures, a young woman’s chastity can be called into question for nothing more than being seen with a man.

If a couple who is in love survives the risks of such a relationship and decides to get married, the formal proposal has to come from the man and his family to the family of the bride. The final say and approval is in the hand of the parents, since marriage is not a personal matter, but a family affair. After acceptance, the next step is making the financial arrangements, a major part of marriage in Egypt. There are many factors to consider in a country with housing shortages, unemployment, and poverty. The parents immediately start discussing the dowry—which the groom pays the bride’s family, the financial responsibilities of the bride and the groom, and the hardest of all, the apartment. In my generation, many young men and women could not get married because of lack of finances and the shortage of apartments. As a result, I saw many engagements broken, and the marriage age began to rise. In the sixties and seventies, because of all our wars with Israel, there was compulsory military service for all young men. They had to serve for up to seven or eight years with very little salary. Many marriages had to be postponed while men were in the military service. Even when discharged from the army, if they survived the war, these men often had little income with which to begin married life. Only the very wealthy were able to get married and afford apartments. The majority had to wait, and many who did marry were forced to live in small crowded apartments with their parents and other siblings.

For many girls and young women in Arab societies, an attempt to follow their hearts has dire consequences and does not usually lead to marriage. The young man with whom she is infatuated could very well end up being the first one to expose her and ruin her reputation. That is why girls have to think twice before entrusting a boy with as innocent a thing as a smile. It is very common for Middle Eastern men to gossip about girls whom they accuse of being “loose” or “easy” for the slightest flirtatious glance. Boys often ruin a girl’s reputation after an innocent date by telling friends and even perfect strangers that the girl seduced him. How does a Muslim young woman know whom to trust? The answer is often no one when it comes to her good name. That’s why dating—or any contact with boys—is such a risky act. Many girls fell in that trap and found themselves in terrible conflicts with their families and male relatives as a result of vicious accusations and lies.

A friend once told me that a certain young man that I hardly knew was claiming I was his girlfriend and that I had initiated a sexual encounter with him. I was shocked by the news. He was someone I had merely seen once at work. I had never dated him. He had never even asked me out. It was a sobering lesson for me to not trust young men.

Boys have an advantage that girls don’t have in such social situations; their reputation is intact or even enhanced if they have relationships. That gives boys and young men a lot of power over girls in a boyfriend-girlfriend relationship. The girl is always the one to blame when things go wrong. The young men can and often do say, “She’s a loose woman; she has no shame.”

But even a careful woman, who shuns relationships, can find herself ruined, particularly if she is poor, with no family, especially no male family to provide protection. An Egyptian young man I knew bragged to me about an incident with a woman he called a “known

prostitute.” He said that when he was about twenty-two years old, he and a friend saw this “prostitute” on the street at night and wanted her to go with them to an apartment. When she refused and fled, they chased her down a street. She ran into a police station. They followed her into the police station and somehow convinced the officers to hand her over to them. They were able to take her out of the police station, into their car, and to an apartment where they both raped her. That woman was simply poor and had no male relatives, therefore no protection, and no respect. Worst of all, the male policemen to whom she went for protection saw nothing wrong with handing her over to her pursuers. Furthermore, the man recounting this story saw nothing wrong with his actions. When I asked him how could he do something like that, he said, “She asked for it.”

That means if you are a poor Egyptian girl, without a father or brother, and decide to wear Western clothing or not cover your head, you are “asking for it.” For this reason, many young women, even though they are secular, chose to cover their heads simply to avoid being looked upon as whores or be subject to rape.

That is the Egypt I did not experience personally since I came from an upper-middle-class family with power and influence. However, women of all classes in Arab society carry a terrible burden: their bodies, their “chastity.”

Ironically, at the heart of Islamic fundamentalism lies the most precious and important object, the woman. She is the source of pride or shame to the Muslim man who rules and is ruled by the most despotic, tyrannical, and humiliating forms of governments on earth. It is a supreme irony that in the world of the Muslim man, the female in his family is the one object over which he may have power.

The Arabic word harim describes women and hormah is singular for a woman; the word’s literal meaning is quite telling—it means “prohibited,” “forbidden,” or “untouchable.” A woman’s physical appearance is a public statement. She is covered and concealed, her virginity is subject to public verification, she suffers ritual female genital mutilation (female circumcision), she is prohibited from exercising most rights enjoyed by Muslim men, and is shackled by sharia (Islamic civil law). Adding insult to injury, she suffers the humiliation of polygamy, a privilege reserved for men.

Honor and sex are very closely tied in Arab culture. Men’s honor is totally dependent on their female blood relatives. Honor is not perceived as being primarily based on personal character, honesty, integrity, and hard work, as it is in many other cultures. It is not even totally dependent on wealth and power. It’s true, that with good character—as Arabs interpret it—a man can enjoy great respect and honor. And wealth and power also command respect. Yet all respect, honor, and good standing in society can disappear in a heartbeat if a man’s female blood relatives do not conform to the strict sexual mores of Muslim society. And the appearance of improper behavior, and not just actual sexual acts, can be just as damaging. When a father marries off his daughter, a virginity check is the traditional requirement in Muslim weddings in order for the father and brothers to declare they have handed the daughter to the groom with honor. But the notion of a man’s honor does not stop with his daughter. Even cousins and other far-off female blood relatives can bring shame and dishonor to a man. This creates incredible paranoia in a culture obsessed with sex and controlling it. No man can command absolute control of all the womenfolk in his extended family twenty-four hours a day.

It’s in fact quite unfair when you think about it; that men’s respect in society could be more dependent on the sexual behavior of their sisters, mothers, wives, or daughters than on their own personal behavior. Thus men feel compelled to monitor the way their women dress, whom they communicate with, who visits their home, and all their comings and goings. It also sets up another case of Muslim culture allowing men to avoid personal responsibility by blaming others.

The Middle East is a place of many contradictions, most of which spring from the extreme compartmentalization of the different roles people play within Arab culture. For instance, despite the extremely prudish moral code on one hand, the overt sexuality of belly dancing is accepted and appreciated by both men and women. This sensual dance is performed at weddings and in all Arab nightclubs, often in the presence of all family members, including children, who sometimes get up and mimic the dancing, as I once did at a Gaza movie theater. However, women who belly dance are looked upon by society as prostitutes. Belly dancers belong to a different and separate class that has very different values and behavior. Arab society sees nothing wrong with such compartmentalization, splitting the good and the bad and seeing each as fulfilling a legitimate role. Only recently have Muslim extremists, who are now very powerful in Egypt, moved to prohibit the centuries-old tradition of belly dancing.

Many of the Arab/Muslim social problems stem directly from the institution of polygamy. The pre-Islamic tribal desert culture in the Arabian Peninsula practiced polygamy for centuries. When Islam came upon the scene in the seventh century, instead of abolishing the practice, it codified polygamy into Islamic law, limiting men to four wives plus any number of slave women. And so this ancient Arabian form of marriage, practiced long before Muhammad arrived, ended up becoming the law for Muslims around the world and in all cultures to this day. A complex of Islamic marriage and divorce laws, designed to protect men’s “honor” and maintain their total control over women, compounds the devastating consequences of this practice.

In addition to the actual laws, a whole array of taboos and social restrictions on women were created to help men control their female flock and thus their honor. These taboos and laws undermine women’s sense of security and respect as partners in marriage, and their relationships to their children, in-laws, and other women, as well as increase women’s dependence on their original family when things go wrong.

In more moderate Muslim countries like Egypt, second marriages are not encouraged but tolerated. And they are usually shrouded in secrecy among the more educated classes. In Egypt, Sunni Muslims practice three forms of marriage. The first is the typical public, official first marriage duly recorded in the courts. A second type is called an urfi marriage, usually done in secret with witnesses but unrecorded with civil courts. Many men who have second marriages prefer urfi marriage because it’s harder for first wives to discover it. A third form is a temporary marriage contract called mutaa marriage, literally meaning “pleasure marriage.” Technically, it is available to both married men and single women, but in practice it is an action initiated by men. This form of marriage, also usually done in secrecy, is for the express purpose of having sex, often for a one-night stand. Under this form of marriage, men can satisfy their lust over any woman for one night, usually in exchange for money (calling it a dowry), and still feel that it is acceptable in the eyes of God. This practice usually boils down to little more than legalized prostitution. Under Islamic law, men have the freedom and many choices to actually legally cheat on their wives, while wives are unable to get a divorce or have a relationship, even when their husband has left them.

How does this affect the dynamics between a husband and wife? Men do not even have to exercise their right to additional wives for the damage to be done. By allowing men to be “loyal” to up to four wives, the stage is set for women always to distrust their husbands. Nor can they trust women friends. Any other woman could shamelessly become an eligible “bachelorette” for one’s husband. Instances of women marrying the husbands of their best friends and having his children behind the first wife’s back do happen.

A single Muslim woman with an eye on a married man can say: “He is a man with a free will to exercise his religious rights to marry another woman. Our marriage will still be blessed by God, just as that of the first wife. He is within his rights to have both of us.” I have actually heard some Muslim women say that. Any man, married or not, can be regarded by a single women as available. Men whose wives are unable to have a baby right after marriage, regardless of who is responsible, are especially likely to seek second

marriages. Egyptian movies often reflect such real-life dramas. Situation comedies are filled with women who seek the help of fortune-tellers or give potions to a husband without his knowledge in an effort to retain his love and keep him from seeking a second wife who can give him the prize of a son. Such comedies reflect the fear of a second wife by desperate first wives.

Many famous movie stars, politicians, doctors, and other wealthy Muslims have more than one wife and many are kept secret. Most presidents, dictators, and men of power in the Arab world have second wives and some even more. Famous examples are the men of the Saudi royal family, Osama bin Laden, and Saddam Hussein.

The end result is an environment that sets women up as adversaries against one another, causing much unnecessary distrust and caution. Competitive relationships among women also deprive them of forming support groups to stand up to the many injustices they are all suffering under. Thus relationships among women in Muslim countries become haphazard, strained, and even hostile. Few Muslim women venture to form relationships outside the family or clan, and very often husbands discourage it. Western-style women’s groups and organizations working for a common cause and to influence change are almost nonexistent in the clanlike Muslim culture. The problem is compounded by fear of envy and the evil eye in Arab society, which is a major Muslim cultural phenomenon. Muslim women, as a result of all these roadblocks, end up having no moral pressure or political muscle to work together to make polygamy unacceptable. Expressing disagreement or any attempts at change are viewed as subversive behavior and outright attacks on Islam.

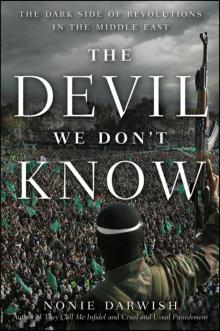

The Devil We Don't Know

The Devil We Don't Know Now They Call Me Infidel

Now They Call Me Infidel