- Home

- Nonie Darwish

Now They Call Me Infidel

Now They Call Me Infidel Read online

SENTINEL

NOW THEY CALL ME INFIDEL

“This is a breakthrough book…. Darwish is one of the most compelling voices for moderate Islam and against extremist violence.”

—John Loftus, president, The Intelligence Summit

“Anyone who wants to understand the real meaning of the clash of civilizations between radical Islam and the West should read this book.”

—Congressman Tom Tancredo of Colorado,

author of In Mortal Danger:

The Battle for America’s Border and Security

“We should all be thankful to Nonie Darwish for writing this insightful book on jihad and the global war on terror.”

—Gen. Paul Vallely, coauthor of Endgame:

The Blueprint for Victory in the War on Terror

“Nonie Darwish…indicts the Middle Eastern and Islamic culture she left behind, exposing what she calls the ‘rigid psychological wall’ imposed by religious and political leaders, the ‘giant machine of oppression’ that dominated society, and the dysfunctional ‘culture of arrogance, pride, and shame.’ Fleeing to the United States, she found happiness—but also a growing infrastructure of radical Islam that she has bravely and effectively confronted.”

—Daniel Pipes, author of

Militant Islam Reaches America

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nonie Darwish was born in Cairo and spent her childhood in Egypt and Gaza. Before emigrating to America in 1978, she worked as a journalist in Egypt. Darwish now leads the group Arabs for Israel and lectures around the country.

Now They Call Me Infidel

Why I Renounced Jihad

for America, Israel, and

the War on Terror

NONIE DARWISH

SENTINEL

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Dehli – 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by Sentinel, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2006

Copyright © Nonie Darwish, 2006

All rights reserved

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Darwish, Nonie.

Now they call me infidel: why I renounced jihad for America, Israel, and the war on terror / Nonie Darwish.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-1012-1785-6

1. Darwish, Nonie. 2. Egyptian American women—Biography. 3. Jihad. 4. Islamic fundamentalism. 5. War on terrorism, 2001–6. United States—Politics and government—2001– I. Title.

E184.E38D37 2006

973'.04927620092—dc22

[B] 2006044360

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed in the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

To the memory of my father, Mustafa,

and to my mother, Dureya

Preface

Shortly after the hardcover publication of this book in November 2006, students from Brown University in Rhode Island invited me to their campus for a discussion, to be sponsored by the Jewish student-run organization called Hillel.

Though I’m accustomed to speaking before large groups of college students, I was particularly honored to speak at an Ivy League university, which represents America’s best and brightest. Free thought, free speech, reason, tolerance, diversity of opinion—all the things that my book laments are deficient in the Arab world, I expected to find flourishing at Brown.

Then something puzzling happened.

The invitation to speak was pulled at the last moment, prompted by Brown’s Muslim chaplain. According to an article titled, “Cancelled Appearance of Pro-Israel Speaker Sparks Controversy,” in the November 27, 2006, edition of the Brown Daily Herald, “In a presentation to the executive board, [Rumee] Ahmed said he believed Darwish’s beliefs are too controversial and potentially disrespectful to the religion of Islam to be invited to speak on campus.”

Brown’s Women’s Center, which had initially expressed interest in my message of expanded freedom for women in Arab society, shockingly stood in solidarity with Ahmed.

Reluctant to challenge this alliance, Brown’s Hillel group revoked its invitation. I was stunned. I am careful never to insult Islam or the prophet Muhammad; what, then is so offensive or divisive about my message? And why would an organization devoted to women’s rights distance itself from an Arab woman who calls for greater respect for women in her native culture? The title of my presentation, after all, was, “The Road to Peace: Women’s Rights.”

The American media paid generous attention to the publication of my book even before controversy erupted, but the “banned at Brown” angle gave new life to the story.

Within a short time, Brown University’s administration graciously stepped forward and reinvited me to campus under its official auspices.

On February 7, 2007, I respectfully addressed a large and diverse audience at Brown. My presentation was followed by a heated (and largely hostile) question-and-answer session.

Several Muslim students angrily critiqued my views, and insinuated that I lacked the academic credentials to hold the opinions I do. I responded that my opinions are based on my experience as a human being who had lived for thirty years in the Middle East.

A young American woman asked me, “Why are you speaking about Muslim women’s oppression? Why not American women’s oppression? Are you implying that Islam is oppressing women?”

I replied that just because I am speaking about the plight of Muslim women does not take away the right of others to speak about the oppression of women in their own cultures. However, I added, one can’t escape the major difference between many Muslim countries and this one: If a husband beats his wife in America, he will be prosecuted under the law. If a husband beats his wife in a Muslim country, his actions are defended by Sharia law.

Then Rumee Ahmed, the Muslim chaplain, asked the last question. He seemed to relish the opportunity to discredit me once and for all. “You mentioned the definition of jihad according to Al Azhar University,” he said, referring to one of the Cairo institution’s publications. “Can you tell me the page number?”

I answered that I did not have the page number with me. The Muslim students around him laughed at me, in approval of their chaplain’s game. Page numbers and reference lines are never needed when you agree with radical Islam; only when you disag

ree.

I did find the page number later in the program, and I asked Ahmed, “If you believe that jihad is an inner struggle, what have you done to alter the views and/or educate the Muslim schools, universities, and mosques across the Muslim world that are teaching jihad as violence and war against non-Muslims?” He did not reply to that question.

I am glad I visited Brown, but I am saddened by how close-minded such a “liberal” community appeared to be.

In early 2007, several prominently placed articles about me appeared in the Egyptian media, denouncing me as a traitor who had dishonored her father’s memory with this book. The mere fact that I support Israel apparently makes me a traitor to Islam, my father, and my country of origin. In their minds, it doesn’t matter that Egypt signed a peace treaty with Israel years ago.

To respond to accusations such as these, I agreed to a number of interviews on Arab and Egyptian television programs, including a half-hour interview on Point of Order, on Al Arabiya TV, which is widely viewed in the Arab world.

Parts of the interview were translated by MemriTV.org. My message to the Arab world in that interview was to view Israel in a different light, a light of tolerance. I was very appreciative that Al Arabiya TV did not edit my words. As a former Arab journalist, I am sadly aware of how common media censorship is in the region. My experience with Point of Order suggested that things might improve in the future.

However, another Egyptian interviewer for Al Arabiya by the name of Ahmad Abdullah put this pointed question to me:

“Do you consider yourself first a Muslim, an Egyptian or an Arab American?”

You should have seen the deep disappointment on his face when I replied, “I am an American…of Egyptian origin.”

That is my heartfelt answer to the troubling question that confronts every Muslim immigrant. We are expected to remain hostages to the ideology of radical Islam and to those who appoint themselves its guardians, even after we have been U.S. citizens for decades.

We are forced to choose between total loyalty to Islam and loyalty to the United States of America. Radical Islam will not allow us to maintain both. Radical Muslims threaten the few of us who, like me, are speaking out—even when we are on American soil.

After twenty-eight years spent living in the United States, I still feel endangered every time I speak out.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank the many people who enriched my life and helped make this book a reality. I thank my husband, Howard, for his help, support, and encouragement; he was the first one to say, “You have a story to tell” at a time when I wanted to block out my past. I am grateful for my children’s love and patience with my long hours of work and many days of travel. Thank you, Laura, Shirene, and Omar. Thank you to Pastor Dudley Rutherford, whose inspiring words elevated my spirit. I thank Uncle Abbas Hafez for being there at a time of need. To my dear friends Selma Alpert and Jacqueline Streiter, I appreciate your friendship, guidance, and encouragement. I also wish to thank the staff of Stand With Us and its national director, Roz Rothstein; the staff of the Israel Project and its president, Jennifer Laszlo; and Minnesotans Against Terrorism and its director, Ilan Sharon.

Thanks to Elizabeth Black for her talent and hard work. She guided the project from start to finish, editing and polishing my words. I also very much appreciate the dedication, tireless efforts, and high standards of Lynne Rabinoff, my literary agent, without whom this book would not have seen fruition. I am indebted to my editor, Bernadette Malone, for her belief in and enthusiasm for my project, as well as to the whole team at Sentinel for their expertise.

And finally, I thank all the people who have written to me over the years; their kind words, encouragement, support, and hope have helped sustain me, and are central to the message of this book.

Contents

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ONE

In the Eye of the Storm

TWO

Growing Up in Cairo

THREE

Living in Two Worlds

FOUR

Marriage and Family Dynamics

FIVE

The Invisible Wall

SIX

A New Beginning in America

SEVEN

The Journey from Hatred to Love

EIGHT

A Second Look After Twenty Years

NINE

Jihad Comes to America

TEN

Arabs for Israel

ELEVEN

The Challenge for America

EPILOGUE

One

In the Eye of the Storm

When I hear a train whistle, I need only to close my eyes to transport myself to a special time and place—to the mid-1950s in the Sinai desert just outside Gaza.

I am eight years old. I am running through a train in complete, unabashed excitement, making those daring leaps between cars while the train rushes across the desert. We are on our way from Gaza to Cairo to see my grandparents. On the train I can be who I am. I don’t have to be so careful. My father is an important man, a military officer in the Egyptian army. We have a special compartment all to ourselves, and the conductor and other staff on the train give us special attention. When I finally settle down to sit and look out the window, all I see is sand and more sand. My sisters and I spot, here and there, familiar groupings of dark Bedouin tents, stark against the white sand, and then we look for the small flocks of sheep and goats tended by Bedouin children and women. Sometimes they turn their backs to us. Other times, they stop to stare as the train passes.

One time our suitcases were all packed and we were ready to leave for the train station in Gaza when we were told the tracks had been bombed, so we had to delay our trip. But this time all is well. We are on our way to Cairo. I love the wonderful, rhythmic choo-choo sound the steam-engine train makes as it chugs across the Sinai. Soon we will cross the Suez Canal and we’ll know we are not far away. My excitement builds as I anticipate arriving in the middle of Cairo, a busy, bustling city with its exciting marketplaces, movie theaters, and cafés. And, of course, the best part is knowing how excited my grandparents will be to see us. They will shower us with gifts and attention nonstop—until the moment we have to say good-bye to return to Gaza. And then my grandmother will cry and so will my mother.

My childhood memories of our trips between Gaza and Cairo remain with me today. In the 1950s it was unusual for Egyptians, even middle-class ones, to travel. So our trips took on an air of indulgent excursion. It was often joked that many Egyptians—even Cairo residents—live and die without ever seeing the pyramids in Giza, which sit on the outskirts of the city.

While in Cairo, life would be a cascade of family outings, endless dinners with extended family—uncles, aunts, cousins—and shopping, lots of shopping. We would start with a trip to a large downtown department store to buy fabric to make our clothes—ready-made clothing was not available in Egypt at that time. Then we’d go to the ancient, narrow, connecting streets of Cairo’s famous bazaar, called Khan el-Khalili, with its many open-air markets selling spices and perfumes, jewelry, hand-painted pottery, exotic fabrics, and sweet, sticky baklava. There my mother would stock up on her favorite spices. And then we’d have the best shish kebab in all of Cairo at our favorite restaurant, El Dahhan—which still exists today—nestled off an alleyway in the Khan el-Khalili.

The train trips back to Gaza were always less exciting. I remember wishing we could stay in Cairo; I felt so safe there. Even though we were returning to the only home I knew at the time, I was dogged by the feeling that we were going back to a place that was not safe. But, looking on the brighter side, we always returned home with treasures—toys, clothing, and tasty treats that could not be found in Gaza. On one trip, I brought home a wonderful doll imported from Europe that said “Mama” and “Papa.” I was thrilled.

On our last train trip back to Gaza—when I was eight years old—the treasure I carried back was a very special birthday

gift from my father and mother, a gold necklace and bracelet inscribed with verses from the Koran and blue beads to protect against the “evil eye.” As on all the other trips, my mother lectured us about how we must not show off our gifts to other children in Gaza or brag about our trips to Cairo. Any show of pride might provoke envy. My mother and grandmother continually reminded us what the Koran says about hasad, which is envy. The evil eye from others, we were told, can take away the good things in life that God gives us. I often saw the old men squatting in the marketplace fingering their blue beads. And now I had the blue beads to protect me as well.

The two things we feared most were the evil eye and Jews. As a child, I was not sure what a Jew was. I had never seen one. All I knew was they were monsters. They wanted to kill Arab children, some said, to drink their blood. I was told never, ever, take candy or fruit from a stranger. It could be a Jew trying to poison me.

My father, Colonel Mustafa Hafez, was a high-ranking intelligence officer in the Egyptian army. I was five years old when President Abdel Nasser assigned him to Gaza and our family moved there. Looking back, I find it hard to believe that Nasser would have put our young, growing family on the frontier of a war zone—or that my mother would have tolerated such a move. But as an obedient Egyptian wife, she knew it was her duty to go with her husband. As did everyone in our culture, she subscribed to the fatalistic view that all was in Allah’s hands. At the time, I was the second-oldest among four children—three girls and one boy. Another sister was born while we lived in Gaza, bringing our family to five children. When we arrived in Gaza, we were driven in military vehicles to our home, a lovely villa with a large balcony, trees, and a garden. The house was surrounded by soldiers and security personnel—armed men who often played with us and drove us to school in jeeps and trucks. I fondly remember trips to the beach with all of us children piled into the back of a truck, riding in the open air. Our favorite soldier, Abdel Halim, who often helped with chores around the house, was clowning around for our amusement and fell off the moving truckbed. We had to knock hard on the window of the truck cab to alert the driver we’d lost one passenger in the dust along the road.

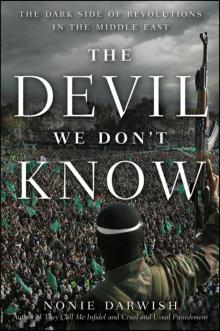

The Devil We Don't Know

The Devil We Don't Know Now They Call Me Infidel

Now They Call Me Infidel