- Home

- Nonie Darwish

Now They Call Me Infidel Page 5

Now They Call Me Infidel Read online

Page 5

Almost from the beginning of Nasser’s presidency, life began changing drastically in Egypt. The war of 1956 had cost the nation dearly, in lives and in economic stability. President Nasser had promised my mother that as the widow of a shahid, the government would pay for our education. But when the school informed her in December 1956 that they had not received any payments, my mother called Nasser’s office. She was told that the number of martyrs was now very large, and the government could no longer pay for all their children’s education. That was a sad day for my mother, who could not afford to keep five children in private schools. However, she did not pull us out of school but decided to dip into her savings to keep us enrolled as long as possible.

Cairo had very little greenery and few parks for children, but there was one very special park that I loved, Anater El Khayreya, near the Nile River. It was a great outlet for children and families, a welcome break from the brutal, noisy, and cramped city of Cairo. I loved the park’s huge eucalyptus trees, ancient plants nourished by the rich Nile soil. There was something solid, stable, and symbolic about these massive, gnarled trees. We held picnics under their shade and swung like Tarzan from their limbs. However, because of the war, the park was neglected and converted into a military zone with barbed wires, bunkers, and dry grass. The trees suffered and some died as yet another casualty of war. Soon one of the nicest areas of that park became off-limits to the public. It was turned into an exclusive vacation resort for the president of Egypt. Little by little, the militarism of Nasser’s Egypt was sapping the goodness out of our life.

My grandmother’s radio was always blasting with the stirring songs of Um Kulthum, the famous Egyptian singer who was adored by the whole Arab world. Throughout my childhood, we were bombarded with calls to war and songs praising President Nasser. Arab leaders were treated as gods and they acted as gods. Fear of Allah was transferred to fear of the dictator. My grandfather once dryly remarked that the radio had more praise for the president than for Allah. Singers competed in pleasing Nasser with their songs of adoration for him. War songs glorifying martyrdom and jihad echoed above all other music over the airwaves of Egyptian radio. The song “Ya Mujahid Fe Sabil Allah,” meaning “Holy Warrior for the Sake of Allah” was a particularly fiery song that inspired war and violence with the following lyrics:

War is the day we all wish for,

Stand up Hero with our swords and join the thousands.

The whole world will witness tomorrow that we are Arabs,

Known for our war heritage that we perfected to an art form.

Hay mujahid for the sake of Allah!

Mujahid, martyrs for Allah.

Such songs glorifying jihad, Arab land, martyrdom, war, and revenge played all day on the radio, and even when the radio was off, they continued playing in our heads. No Arab could avoid the culture of jihad. Jihad is not some esoteric concept. In the Arab world, the meaning of jihad is clear: It is a religious holy war against infidels, an armed struggle against anyone who is not a Muslim. It is a fight for Allah’s cause to promote Islamic dominion in the world.

To ensure this dominion, it was necessary to be in control of the minds, hearts, and souls of all citizens. And nothing was more effective than for Allah’s command for jihad to be presented in the musical rhythm of songs, as well as the moving and hypnotic Koranic recitations, which confirmed the call for jihad in Allah’s own words.

I liked to listen to the call to worship that rang from the mosques five times each day. These calls, which echoed from loudspeakers on the mosque’s minaret, were very beautiful and awe inspiring. But that call was often followed by fiery sermons that exhorted Muslims to destroy the Jews and infidels, the enemies of God. The sheikhs preached that the highest rewards and honor will be bestowed upon those who die in the cause of jihad. The call to war and the pride of giving up one’s life for the sake of Allah was everywhere in the popular culture.

Sometimes I was ashamed by my own anger over my father’s death in jihad, since that could be interpreted that I was not a good Muslim. I had to hide my feelings and pretend that I was a good Muslim. My mother never forced us to become devout Muslims, since, at that time, Egypt was more secular than other Muslim countries. As did many others in my generation, I rebelled against praying five times a day and fasting during Ramadan. My grandparents and their generation seemed to be the only ones who prayed and fasted regularly. But devout or not, no one could escape the impact of the culture that ruled every aspect of our lives. And while my mother did not require that we be devout in day-to-day practice, she did want us to learn to be good Muslims generally. In fact, my mother sometimes brought in a sheikh to recite the Koran in our home. Even though I did not understand much of the meaning of what he was reciting, I enjoyed the way it sounded and felt good about the blessings the sheikh was giving our house. It helped answer my needs for a connection to something holy. While he was reciting, my mother would burn incense and walk with him all around the house. It made us feel that our home was blessed.

I once asked the sheikh why there were so many poor people, saying that it didn’t seem fair to me. He answered that I was not to feel too bad because it is Allah’s will and that they deserve the poverty they are in since Allah gives everyone what they deserve. I did not like his answer but did not dare tell him that. As I was leaving the room, he reminded me to always say “in Shaallah,” which means “if Allah is willing.” I said, “Of course,” and then dutifully repeated “In Shaallah.” But I did so with a sigh of slight revolt. I always hated to be reminded to say it. Everyone around me was so fatalistic. Even as a child, I sensed something wrong with that fatalism. We were expected to say this phrase in almost every conversation, but especially whenever we spoke about a plan or a decision. If I did not say it, I was stopped right in the middle of my conversation and ordered—or “reminded”—that it was not good to speak about plans or decisions without saying in Shaallah. Unless you said the magic words, your plans would be cursed and without Allah’s blessings.

While the sheikh who visited our home taught that the poor people’s condition was Allah’s will, I received a very different view of the poor from the nuns at school. That same year, when I was twelve, the nuns took us to an Egyptian village on the outskirts of Cairo, where we visited a mud house. The nuns were very respectful and told us to greet the lady in the house properly. They gave the woman a bag as we left, probably food. I was surprised that the nuns cared about people who most Cairo dwellers, especially the wealthy, looked down upon. These people were a part of Egypt we didn’t know.

Social classes in Egypt were very stratified. We never mingled as equals. Furthermore, it was very hard, if not impossible, to move upward from the class you were born into. That was how Egyptian society had functioned for generations. The upper classes treated the lower classes with arrogance and resentment—and sometimes worse. The way a higher class treated the one below it could be very cruel and unjust. I have seen men slap poorer men on the face for the slightest mistake or error. Even women abused poorer women, especially maids. The law did not protect the poor and the weak in society. When we drove by poorer neighborhoods, especially delta villages on the way to Alexandria, it was almost like being in a foreign country. These delta peasants spoke with a different accent than city people, dressed differently, and behaved differently. They lived in mud homes covered by branches and hay. Their children were barefoot, malnourished, and filthy. Women could be seen carrying large, heavy clay containers as they walked to a Nile branch to get water. Some of the women had ankle bracelets called kholkhal and tattoos on their foreheads or arms. They washed their clothes as well as drank from these same Nile River branches, even though the water was known to be contaminated with a multitude of germs and diseases. Intestinal bilharzias is a widespread disease afflicting many Egyptians, especially peasants who have direct contract with water from the Nile. Despite their harsh life, these peasants seemed content with the life Allah had given them and did not st

and up for their rights. The notion of in Shaallah seemed to govern at all levels of Egyptian society. Dictators neglected the peasants, called fellaheen in Egypt, since their condition was God’s will. Ironically, Egyptian fellaheen were actually among the few hard-working segments of the population. Many Cairo people had government desk jobs and avoided hard work, especially when the boss was not around. Despite their extreme poverty and hard life, the fellaheen demanded little from the government and were happy to be left alone outside the sphere of harsh government bureaucracy and mismanagement. The Egyptian word fellaheen also had another derogative meaning in Cairo slang; it meant “ignorant,” “low class,” and “lacking good taste.” The fellaheen who fed Egypt were the least respected by Egyptians. And the government neglected these rural areas—at that time most villages did not have electricity, proper schools, or hospitals. By now, Egypt has improved many of the conditions in these villages, but improvements never seem to keep pace in a country whose population multiplies very rapidly.

My best friend at St. Clare’s was an Armenian girl named Alice. She was gentle and sweet, and her family was more Westernized than many of my Egyptian friends. I enjoyed being with Alice and her family. I felt I could let my guard down around them. When we were sixteen, much to my disappointment, Alice’s family left to emigrate to Canada.

While the majority of Egypt was Muslim, there had once been thriving populations of Jews, Armenians, Coptic Christians, Greek Orthodox, and other groups. For centuries, both Cairo and Alexandria were bustling cosmopolitan centers with diverse cultural influences, serving as home to many artists and intellectuals.

Many Jews were forced out of Egypt in the 1950s. Some were accused of espionage after the 1956 war. I was very young, but I seem to recall seeing pictures in the newspaper of two Jews who were hung as traitors. During the 1956 war, some Egyptians called on everyone to turn off their lights, and if anyone did not, it meant that they were traitors who wanted to draw attention so Israeli planes could hit Cairo. The two Jews who were tried as traitors and executed came from prominent, wealthy Jewish-Egyptian families. After the war, most Jews left Egypt penniless, having been forced to leave behind their businesses and homes. When their possessions were auctioned off, the military had first crack at them—one of the many military officers’ perks. I remember my mother going off to these auctions where precious furnishings could be had for a fraction of their worth.

With tears in her eyes, my grandmother once told me how her Jewish best friend was evicted from Egypt and how the woman did not want to leave the only country she had ever known. My grandmother described how her friend—one of the kindest and best human beings she had ever known—had to be literally pulled out of her apartment by her family. Other minorities who felt unwelcome after the revolution also left Egypt, many of them by choice when Nasser nationalized all businesses and began pursuing a socialist agenda. The country lurched into a rapid decline—economically, culturally, and politically.

Egyptian Christians (called Copts) with nearly two thousand years of historical ties to Egypt now began suffering the impact of radical Islam as well as Nasser’s socialism. They also reluctantly chose to emigrate to the West in large numbers. Historically speaking, Copts could be considered more authentically Egyptian than Muslims, because they were the ones who resisted forced conversion to Islam when the Arabs invaded Egypt in the seventh century. Nevertheless, Copts endured a second-class citizenship and derogative names, such as “blue bone,” which harkened to the day when they were forced into hard labor, resulting in blue marks on their bone-thin bodies. Copts comprised about 15 percent of Egypt’s population when I was a child. By now, due to emigration, they have shrunk to less than 10 percent.

The once diverse culture of Egypt started shrinking to mostly Egyptian Muslims. Anyone who did not appear 100 percent Egyptian was called khawaga, meaning foreigner. Egyptians of Greek and Armenian origin whose families had always lived in Egypt were considered khawaga even though they were Egyptians by birth. An Armenian friend once confided in me how unwelcome and insulted her father felt when people called him Khawaga instead of his real name. The few minorities who remained in Egypt into the late 1950s—mostly Armenians and Greeks—eventually began emigrating to the West as well.

By the 1960s, after Nasser’s rigid socialist rules began taking effect, even ordinary Egyptians Muslims began looking toward the West. Nasser tried to stem the tide by clamping down on exit visas. It became harder and harder to leave. Until then, emigration was unthinkable among most Egyptians, who valued their strong ties to their land and history. But by the mid-1960s, extreme poverty and the heavy-handed, despotic rule of Nasser forced many Egyptians to seek work in any country that would take them.

The Egyptian film industry in the 1940s and 1950s was thriving, and all Arab countries regarded Egypt as the cultural center of the Arab world. But as talented people—many of them Egyptian Jews—left the country, the once world-class movie industry deteriorated, ending an important part of the Egyptian cultural scene. The quality of Egyptian movies is now so poor that most Egyptians don’t bother to watch them.

I fondly remember the great Egyptian films and movie stars of the 1950s, especially Faten Hamama, the most popular actress in Egypt and indeed the whole Arab world. Faten Hamama was the former wife of Omar Sharif. At the time of their marriage, Sharif was the lesser well known of the two. Born in Egypt to a prominent Lebanese/Syrian family, Omar Sharif was Roman Catholic and converted to Islam in order to marry Faten Hamama. Sharif starred in great classic Egyptian movies, such as Fi Baitina Rajul. But he later skyrocketed to international fame when he won roles in Lawrence of Arabia and then Doctor Zhivago. However, when he played opposite Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl, he was branded a “Jew-lover,” and his films were banned in Egypt. Another bit of movie trivia: when Elizabeth Taylor converted from Christianity to Judaism, her films were prohibited in the Arab world. So Egyptians never saw the movie Cleopatra. Few Westerners can comprehend the degree to which hatred of Jews permeates every aspect of Arab culture.

Long before anyone had heard of Omar Sharif, Faten Hamama was the great movie diva of the Arab world. I adored her. Women and girls throughout the Arab world identified with Faten Hamama’s portrayals of Arab women. She played her characters with sincerity, elegance, and class, creating a role model for us all. Her best-known film, Doa al Karawan (Prayers of the Nightingale) was adapted from a novel by Taha Hussein, a giant of modern Arabic literature. It is both a love story and a tale of revenge. When a girl who worked as a maid is raped by her boss, her uncle cleanses the family honor by killing her. The film resonated with Arab women, not because it was some far-fetched melodrama, but because it described an all-too-familiar tragedy in Islamic culture.

When I was sixteen years old, a new maid who was about my age came to work in our household. I believe her name was Hosneya. When my mother suspected Hosneya was pregnant, she took her into a room and closed the door and talked to her for a long time. After they came out, my mother looked frightened and distraught. She would not tell us girls what it was about at the time. But later she explained it to us. Hosneya’s previous boss had raped her, and when his wife caught him, she kicked the girl out, blaming it all on her. Shortly thereafter, Hosneya came to work at our home.

Our new maid’s condition placed my mother in a terrible dilemma. So she sat down with my grandparents to seek their advice. She had to make a difficult decision. If my mother sent Hosneya back to her family, they might kill her. But if we kept her in our home, perhaps one of our male relatives or friends would be accused of causing the pregnancy. My mother came to what she believed was the best decision. She sent Hosneya to a government facility that took in pregnant girls.

Several months later, the domestic employment agent who had originally placed the girl in our home visited us. We asked him how Hosneya was doing. His answer to my mother was “May Allah prolong your life, Madam,” which is the polite Egyptian way of saying someone has die

d. Stunned, we asked him what happened. He simply said, “Her family took care of her disgrace.”

To this day I cannot forget Hosneya’s face.

Egyptian history textbooks written prior to the 1952 revolution were trashed and rewritten. The new books—and the media—ignored the fact that the same corruption during King Farouk’s time was doubled and tripled by the idealistic, inexperienced revolutionary officers who took over the government in 1952. We learned only the negatives of Egyptian history prior to 1952. While the rest of the world’s students studied about the glories of ancient Egypt, the pyramids, and the lush agriculture of the Nile Valley, we knew little beyond the vitriolic rhetoric against Zionists and Western imperialists. My contemporaries and I graduated from high school knowing very little about ancient Egyptian pre-Islamic history. Textbooks and Egyptian media glorified defiant and revolutionary figures such as Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. That was especially true after the United States refused to go along with Nasser’s plans for increased armaments and the building of the Aswan Dam. Countries that defied the United States, such as Cuba, and later on Vietnam, were seen as heroic states by the Arab media. Any defiance of the United States as a superpower was envied and romanticized by the culture of jihad.

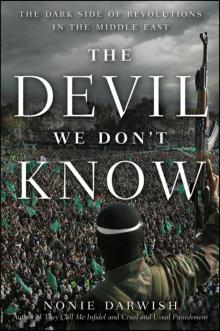

The Devil We Don't Know

The Devil We Don't Know Now They Call Me Infidel

Now They Call Me Infidel